| Solar Cookers International 1919 21st Street, #101 Sacramento, CA 95811 USA Tel. 916-455-4499 Fax 916-455-4498 E-mail: info@solarcookers.org |

Solar Cooker Review April 2000 |

Solar Cooking

Archive: |

| Volume 6, Number 1 Back Issues E-mail PDF |

|

In This Issue

- Projects Clearly Valued

- President's Corner

- Letters

- News You Send

- Portrait of a Popular Parabolic Cooker

- An Easier Way to Build Your Own Solar CooKit

- Solar Cooking in India

- What it Means for SCI to Receive a $25,000 Contribution

- Crossroads

- Upcoming Event

- International Standards for Testing Solar Cookers

- Memorials

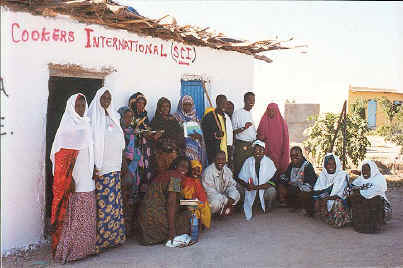

by Terry Grumley

Energizing! Inspiring! These are the words that best summarize my January

visit to SCIís pilot projects in Africa. While I was able to get a sense of

SCIís strengths in my first two months work in Sacramento, it wasnít until I

visited the field that I could fully appreciate all the effort that has gone

into developing these pilot projects and the positive results they are showing.

Energizing! Inspiring! These are the words that best summarize my January

visit to SCIís pilot projects in Africa. While I was able to get a sense of

SCIís strengths in my first two months work in Sacramento, it wasnít until I

visited the field that I could fully appreciate all the effort that has gone

into developing these pilot projects and the positive results they are showing.

The development of an effective system of support to the projects in the different economic, cultural and social settings of Kenya, Ethiopia and Zimbabwe from the central office in Sacramento has been a major achievement. Meeting the challenges that stem from the remoteness of the refugee camps within Ethiopia and Kenya as well as working with different management structures and different partners within each country has not been easy. The strong base established through volunteer trainers, board members and advisors and our former executive director, Beverly Blum, became a springboard to take major steps forward to the current structure where program country staff manage the solar cooking projects.

All our projects are proceeding well and producing benefits that are clearly valued by both the users of solar cookers and the partner organizations with which SCI works. Partner organizations demonstrated their continued support of solar cooking projects in all three sites by agreeing to extend or renew written agreements. SCI staff and trainers are competent and highly motivated, continually developing new ideas and improvements to the programs.

Valuable networks with other development and renewable energy organizations have been established in each country. Local manufacturers for bags and CooKits have been identified in Kenya and Zimbabwe, and SCI has established offices in both Kenya and Ethiopia. In Zimbabwe, our partner organization, the Development Technology Centre (DTC), has expanded its solar cooking program in which CooKits are sold, not given, providing a key element for sustainability.

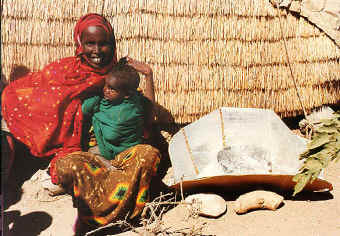

After three days of travel from Nairobi, the reward was a panoramic view of the Aisha Refugee Camp with a lovely pattern of CooKits flashing out from between the tokols (the homes of the Somali refugees with whom we work). Seeing this wide display of our beacons of environmental sustainability was a great way to start the trip. During that first day of my visit to Aisha Refugee Camp in Ethiopia, Margaret Owino, SCIís East Africa Representative, and I had to search hard to find a family that wasnít using a solar cooker to prepare a mid-day meal. Overall, we estimated use as over 50% - strong evidence for the acceptance of solar cookers in the refugee familyís everyday routine.

Community leaders and elders, solar cooks, local partner staff and surrounding community representatives expressed their enthusiasm for the project and its benefits. Of the approximately 2000 families in the camp, 98% have received a CooKit.

An elder from the community outside the Aisha camp said that his people have

seen the cookers in the camp and are always asking him when solar cooking might

become available to them--another sign of the great opportunities for solar

cooking to ease suffering, shortages and environmental destruction. One solar

cook valued her CooKit so much that when the panel tore from normal wear, she

actually sewed the piece of panel back on to keep it in operation. Another

explained the important benefit to her of the time saved using a CooKit, which

she can now devote to activities with a womenís group.

An elder from the community outside the Aisha camp said that his people have

seen the cookers in the camp and are always asking him when solar cooking might

become available to them--another sign of the great opportunities for solar

cooking to ease suffering, shortages and environmental destruction. One solar

cook valued her CooKit so much that when the panel tore from normal wear, she

actually sewed the piece of panel back on to keep it in operation. Another

explained the important benefit to her of the time saved using a CooKit, which

she can now devote to activities with a womenís group.

An especially impressive achievement has been the introduction of a plastic bag re-using program by SCI. CooKit users have been trained how to weave very high quality baskets, ropes, bags and other household items using worn-out plastic bags. The result has been a dramatic reduction in the plastic pollution around the camp. This approach makes use of a skill that is already part of the culture, but that can be applied to a new problem with a little adaptation. The local Ethiopian refugee support agency was so impressed that they asked us to extend the recycling program to other camps.

With the hiring of Nadir Aden Hassan as Project Coordinator last year, the

project has made positive strides forward. Trainers have increased their

promotion activities, generating more enthusiasm for the project. Nadir has

enabled closer coordination with our partner organization, United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Though families have extremely limited

income, they were still able to demonstrate a commitment to the project by

planting trees in return for a CooKit. This exchange was possible through

coordination between SCI and UNHCR.

With the hiring of Nadir Aden Hassan as Project Coordinator last year, the

project has made positive strides forward. Trainers have increased their

promotion activities, generating more enthusiasm for the project. Nadir has

enabled closer coordination with our partner organization, United Nations High

Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Though families have extremely limited

income, they were still able to demonstrate a commitment to the project by

planting trees in return for a CooKit. This exchange was possible through

coordination between SCI and UNHCR.

Cooking bags are now available locally and an additional 1000 CooKits have been cleared through customs and are on their way to the camp. These new CooKits will be used as replacements for worn-out cookers and will enable larger families to obtain a second cooker.

Since it was cloudy during the time of our visit to Kakuma Refugee Camp, we saw no CooKits in use; however, interviews with individual users verified the information we received from SCI trainers and partner organization staff that solar cooker use is widespread. Previous surveys (Knudson & Lankford) have shown a 25% to 50% fuelwood savings for families using solar cookers on sunny days.

Our partner organization is Lutheran World Federation (LWF). LWF plays a strong role in the administration of the project, from supervising field staff to inventory, storage and shipment of cooker supplies. While the percentage of the population who have solar cookers is smaller in Kakuma, the absolute numbers are larger (9,500+) than in Aisha, reflecting the larger size of the continually growing camp.

Solar cooks, trainers and LWF staff were enthusiastic in their calls for continuation and expansion of the project. I was struck by the story of a grandmother living alone who could not afford to have her ration of dried corn (maize) milled and could not afford the firewood necessary to cook unmilled corn. Solar cooking the corn solves her problem, giving her a way to eat her meals. Such stories of the difference solar cooking makes--between hunger and being able to eat--abound in Kakuma.

We also met with representatives from a womenís group from the Turkana community (local residents of the region) and discussed providing some further training. We asked the group for help in making some experimental solar cookers with Turkana basketry covered with foil. The activity by trainers to promote construction and/or repair of a limited number of homemade cookers (using cardboard and shiny gift wrap) seems to be making some progress.

Tentative plans were made with the German Technical Cooperation agency (GTZ) that promotes fuel-efficient wood stoves to cross train both SCI and GTZ extension personnel in the use of both fuel efficient wood stoves and solar cookers.

The production of CooKits and bags within Kenya is a definite plus for the project.

The Zimbabwe program is different from Aisha and Kakuma in three ways:

- The users of solar cookers are in the general population (per capita GNP under US $700), yet are able to buy their own CooKits.

- SCI works under a Letter of Agreement with the University of Zimbabwe's Development Technology Centre (DTC) which implements the project. (In the Kenya and Ethiopia projects we have SCI employees who are responsible for supervising and reporting on the project.)

- DTC acts as the lead organization to coordinate the implementation of the project with a group of other Zimbabwe non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that work in the communities where the projects are carried out.

That people are willing to use their own funds to purchase solar cookers speaks well of the project.

The Zimbabwe project has grown from two communities involved at the beginning to six now. Visits with trainers of two of the communities in which we work revealed widespread enthusiasm and demand for the CooKits. DTC receives frequent requests from communities outside the project areas to start solar cooker projects.

DTC is in the process of designing selection criteria for future project sites combining the criteria of intensity and duration of sunshine, scarcity of vegetation/trees and population density. This more systematic approach to site selection takes into consideration prime factors that influence the outcome of projects.

The primary involvement of DTC and other Zimbabwe NGOs, along with DTCís favorable relationship with the Zimbabwe Department of Energy, is a major, positive factor for the long-term sustainability of the project. DTC has also developed relationships with a wide range of other organizations that work in related areas.

The local production of CooKit panels and cooking bags at very reasonable cost is also a major factor for sustainability.

The Zimbabwe project holds a particular promise of becoming self-sustaining in that solar cooking trainers may be able to earn a reasonable income through their training activity and sales of CooKits. However, this has not yet proven itself in practice. DTC, with input from SCI, will soon be contracting with a Zimbabwe organization with a proven record of success in such micro-enterprise development to examine this issue and to prepare a more comprehensive plan for moving ahead.

Challenges

There are a number of challenges that are important to address. While there is an obvious high demand for solar cookers in each country, we have limited resources that must be applied selectively. We must guard against spreading our efforts too thinly and must insure the provision of sufficient support services including training and follow-up. We must take into account not only the needs of individual solar cooking families, but also the factors in each location that influence the chances for success and the expected overall impact of our projects on families and the environment.

In Ethiopia, there is demand for heavier CooKits that will be less susceptible to being blown by the wind. Families would also like cookers that cook faster, which presents a major technical challenge if cooker costs are to be held down. The need to replace cooking bags frequently is also a concern. The difficulty in finding an Ethiopian producer to make CooKits continues to require importation of cookers, which can take months and may not always be feasible.

Though SCI has been in existence for eleven years now, the organization is still relatively new to the "overseas development" process, and, consequently, we can benefit from focusing more attention on improvement in the design, implementation, and evaluation of our projects. With more detailed objectives, budgets and monitoring criteria, we will be better able to support, supervise and advance our projects.

Moving Forward

One can easily see that SCI has made impressive progress with our pilot projects. These projects, the resources mobilized to launch and maintain these projects and the experience gained provide our organization with a solid base for future growth and the pursuit of its mission to spread solar cooking.

The next logical step is to promote solar cooking on a larger scale within the region of eastern and southern Africa where we are currently focused. It will be necessary to delegate more responsibility and authority to the program staff already positioned in these countries and to continue to build their capacity. With that increased capacity, SCI will be able to support and guide other organizations in the dissemination of solar cooking technology, resulting in reduced suffering, empowerment of a wider population of solar cooks and reduction of deforestation within these countries.

As the SCI Board and staff work together in the year ahead, we will plan for taking this next step. While some tasks are very clear, others are still taking shape. We welcome your ideas as we respond to this challenge.

by Christopher Gronbeck

In recent years, solar cooking has acquired new international urgency: It is crucial not just in dramatically improving the lives of women, children, and families in developing nations, but in serving a pivotal role in any lasting solution to global climate change. A solar cooker relieves pressure on forests when it displaces the use of wood for fuel, thereby preserving precious biological carbon stores. Solar cooking at once addresses the needs of the individual and the needs of the planet, humbly revealing the interconnected nature of our world.

We are blessed with a truly splendid solution Ö a solar cooker is small, lightweight, inexpensive, reliable, safe, and easy to use. It is customizable to local cultures and is powered by the gift of abundant sunlight. One of our biggest challenges is to spread the news that something so simple can work so well in today's technologically brisk world.

At SCI we consider ourselves extremely fortunate to welcome the new century in the company of an outstanding new executive director, a wonderful and enthusiastic staff, a board brimming with new energy, and a legion of dedicated friends and supporters. We simply can't wait to plunge into the exciting year ahead of us, and we hope you accept the challenge and join us to make this the decade that the world rediscovers the elegant beauty of cooking with the sun.

I have supported Solar Cookers International for a number of years, have attended an SCI workshop in Sacramento, have made several solar ovens myself and taught others to do so, use a solar box cooker regularly during the summer, and take every opportunity to share what I know about solar cooking and the activities of SCI with others.

While your August 1999 letter included some valid, cogent points regarding the benefits of solar cookers as an alternative to fire in other parts of the world, I am concerned about the focus on other parts of the world, when we need to be focusing at least equally on our own part of the world.

It seems to me that Americans need to be reminded that there is an alternative to fossil fuels. It is easy enough to write out a check to SCI and think that we are supporting a valuable development project, but I believe that we must also take steps in our own lives to transform current short-term thinking of non-sustainable [fossil fuel] dependence to the long-term thinking of a sustainable future with solar energy as a partial energy source right here.

I have lived and worked in Africa and the West Indies for nearly twenty years and am entirely supportive of and, indeed, enthusiastic about the work that SCI is doing in the rest of the world, but I wonder how many of the Americans who contribute to SCI are actually reducing their own depletion of the earthís scarce resources.

C. Cox

Willits, California

USA

Please find enclosed a check from Blackhawk Council Girl Scout Troop 46 for $33 to provide one family with a solar cooker, supplies and training.

Girl Scout Troop 46 is working on a badge called "Ready for Tomorrow." One of the things we did towards earning this badge was to review donation literature from five organizations. We looked at what each organization does to help plants, animals or people, considered how these actions help the environment, and what types of actions are funded by recommended pledges or donations. We then voted to provide financial support to one or more organizations.

Our troop felt Solar Cookers International was the best organization to support financially because it saves trees, decreases pollution, helps decrease global warming, uses solar resources wisely and helps people. We wish you great success in continuing this important work worldwide, and we are glad we can help.

Girl Scout Troop 46

Middleton, Wisconsin

USA

AFRICA AND EUROPE

CAMEROON

Ms. Marguerite Essama, president of ASFERUCAM (Association des femmes Rurales du Cameroon) writes to reaffirm their dedication to the cause of solar cooking. The organization has been working with the government to popularize solar cooking for the sake of women, as well as for their forests, which are being rapidly destroyed. The group is launching a national seminar in March of 2000, to show people how to make and use solar cookers. Contact: M. Essama, ASFERUCAM, B.P. 195, Ebolowa, Cameroon.

THE GAMBIA

Solar cooking advocate Mr. Saikou M. Jarra reports on three recent solar cooking demonstrations performed by the Tubanding Earth Savers Club. The first was held August 11, with over 100 people attending, including local dignitaries. A national wildlife officer participated in the demonstration by speaking on the importance of solar cooking to protecting the environment. The second and third, held at the villages of So lo la Mandinka and Koro jula Kunda respectively, emphasized how solar cooking can ease suffering of women. Local womenís groups were so impressed that they formed cooks clubs to continue to spread the technology. In response to the excitement in these two villages, the Club built cookers for the villages to keep.

The Tubanding Earth Savers Club recently developed "Project 2020," aimed at promoting solar cookers and solar energy throughout the Central and Upper River Districts. The initiative begins on the 20th of March. The Club requests assistance in the form of funding, materials, cookers or volunteer time. For information on the demonstrations or to help with Project 2020 write to S. Jarra, Earth Savers Club, Tubanding Village, Bansang Post Office, Central River Division, The Gambia, or telephone Alhagie Jarra at 674044.

MADAGASCAR

Josephine Andrews, interim instructor for the Madagascar-California Alliance project in Nosy Be, reports the following cooking times realized in their stovetop solar cooker: fried fish, 45 minutes and omelettes (sold to tourists as a snack), 15 minutes. Their panel cookers are still being used to bake cakes which are ever popular with tourists. Contact: Edward Metz, MCA, 537 Jones Street #780, San Francisco, California 94102, USA, tel: 415 441 6042, email: 102517.3557@compuserve.com

NETHERLANDS

Ms. Renee Blom writes of a low-cost solar cooker that can be used indoors. Made mostly from re-used waste paper, the cooker is glued against the inside of a window in the house. The window must be inclined or angled and should be situated to receive lots of sunlight. The window lets sunlight into the cooker where it is trapped as heat energy. The cooking pot is placed into or taken from the cooker through a small back door in the cooker. More details about manufacturing this cooker, which requires no glass other than the house window, can be found in the book "Appropriate Paper-based Technology" by Bevill Packer, published in London in 1995 by Intermediate Technology Publications (ISBN: 1 85339 268 5).

THE AMERICAS

MEXICO

Mr. Miguel Angel Marquez Alvarez and his wife Margarita Lopez Hernandez conducted a solar box cooker class for nuns at a national convention. Eight cookers were constructed and all function well. The nuns now promote these cookers as they travel around the country. Contact: M. Alvarez, Fontaneros #107, Colonia Hacienda Echeveste, Leon, Guanajuato, Mexico 37100, email: mmarquez@wtsmexico.com.mx

PERU

Mr. Chris Keavney conducted a solar cooking course in Inka Pukara last May. The women participants continue to use the cookers months later. The cookers are primarily used for baking bread, which is difficult to do with traditional wood stoves. The bread is then shared among the women as dessert. Contact: C. Keavney, Misioneros de Maryknoll, Casilla 295, Puno, Peru, tel: 51 54 85 4070, email: ckeavney@mkpuno.inv.pe

UNITED STATES

Arizona

Solar cooking expert Barbara Kerr provides a simple method of comparing the performance of two or more cookers. With the cookers side-by-side on a sunny day, put 1/4 cup rice and 1/2 cup water in identical, black-colored "soup" cans covered with a small piece of clear glass, and place one in each cooker. Without opening the cookers (or bag in panel cookers), watch for rice rising to the surface of the water. The first one to rise is the hottest. Contact: B. Kerr, email: kerrcole@frontiernet.net

Ms. Ethel Farnsworth taught a course entitled "Technology and

Application of Solar Cooking" at Arizona Western College this past fall.

Topics included history, construction, maintenance, and use of solar cookers.

Contact: E. Farnsworth, email: evrhode618@aol.com

Ms. Ethel Farnsworth taught a course entitled "Technology and

Application of Solar Cooking" at Arizona Western College this past fall.

Topics included history, construction, maintenance, and use of solar cookers.

Contact: E. Farnsworth, email: evrhode618@aol.com

ASIA AND PACIFIC

IRAN

Longtime solar cooking promoter Ms. Gabi Cook organized several events in 1999. Two of the gatherings brought local women together to share solar-cooked food and discuss solar cooking in Iran. Using a CooKit they cooked beef stew with legumes and baked cakes and scones. Among the participants were representatives of Cenesta, an environmental NGO, and others working with refugees and women in development. One outcome of these events was the formation of the Solar Cookers Network - Tehran. Gabi also organized a solar cooking fair for students ages 12-15 at the school where she taught. They made CooKits and learned about cooking with the sun. Here are some of their comments:

- Djenabou Sou

For more information, email Gabi at petegabcook@hotmail.com

VIET NAM

Mr. Nguyen Tan Bich has crafted quality solar cookers using local

materials. His cookers consist of a well-insulated basin situated inside a woven

basket, with a glass top and reflective lid. Nguyen reminds us of the many

benefits that solar cooking will provide his country, particularly the central

and northern provinces which receive 2-3000 hours of sunlight per year. Solar

cooking helps:

Mr. Nguyen Tan Bich has crafted quality solar cookers using local

materials. His cookers consist of a well-insulated basin situated inside a woven

basket, with a glass top and reflective lid. Nguyen reminds us of the many

benefits that solar cooking will provide his country, particularly the central

and northern provinces which receive 2-3000 hours of sunlight per year. Solar

cooking helps:

- reduce dependence on polluting fossil fuels

- preserve forests and soil

- save time and money

- prevent lung and eye diseases caused by smoky fires

- free children from the burdens of fuelwood gathering so they can attend school

- improve health by allowing nutritional, longer-cooking foods, such as maize and beans, to be cooked by people who canít afford to normally cook them due to fuel expense

- reduce water-borne diseases through solar water pasteurization

For more information contact N. Bich, Hop Thu So 1, Buu Dien Thach An Xa Binh My, Huyen Binh Son Tinh Quang Ngai, Viet Nam.

Portrait of a Popular Parabolic Cooker

Over 6,000 SK12 type solar cookers have been installed in more than 60 countries worldwide.

The SK family of cookers represent a different approach from the very simple solar cookers (box type and CooKit or open panel type) with which Solar Cookers International has been most involved. The SK cookers, however, do have proven appeal for some users and for a number of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that work in international development. The SK line represents another option for those struggling to ease fuelwood shortages.

The SK cookers are parabolic dishes approximately 1.4 meters in diameter.

They are designed with a deep focus (the focal area is inside the dish). The

deep focus substantially reduces the possibility that users or their children

will suffer burns; the deep focus also means that tracking the sun is fairly

easy, since the cooker does not need to be repositioned more than every 20

minutes. Additional safety and convenience features include a tracking indicator

which makes it unnecessary to look at the sun while positioning the cooker, as

well as a simple mechanism for swinging the reflector out of the sunshine to get

safe access to the food. Instead of a focal point, the sunlight is focused over

a somewhat wider area where the cooking pot is always mounted--further reducing

the risk of serious burns. Having a large, dark pot in that focal area also

reduces the chance that users or their families will be dazzled by glare from

the cooker.

The SK cookers are parabolic dishes approximately 1.4 meters in diameter.

They are designed with a deep focus (the focal area is inside the dish). The

deep focus substantially reduces the possibility that users or their children

will suffer burns; the deep focus also means that tracking the sun is fairly

easy, since the cooker does not need to be repositioned more than every 20

minutes. Additional safety and convenience features include a tracking indicator

which makes it unnecessary to look at the sun while positioning the cooker, as

well as a simple mechanism for swinging the reflector out of the sunshine to get

safe access to the food. Instead of a focal point, the sunlight is focused over

a somewhat wider area where the cooking pot is always mounted--further reducing

the risk of serious burns. Having a large, dark pot in that focal area also

reduces the chance that users or their families will be dazzled by glare from

the cooker.

A stable stand for the parabolic dish and a simple system for turning it upside down when not in use also contribute to safety and convenience.

The SK cookers can cook all kinds of foods. A big advantage over simpler cookers is that the SK cookers can fry foods. They are impressively powerful--they can boil 48 liters of water per day. They can cook from about two hours after sunrise to two hours before sunset in the sun, but frequent repositioning is needed when the sun is very low in the sky.

The latest cooker in the SK series (SK98M) can be separated into two parts for easy storage in the house at night. The base of the cooker can then serve as a table while the reflector can be used to amplify the light of candles or lanterns.

According to Dr. Dieter Seifert of Neuotting, Germany, who developed the SK cookers, the materials cost about 60 Euro (about US $60), mostly for a set of thin, but sturdy, anodized aluminum sheets which reflect the sunlight into the focal area where the cooking pot is mounted. These sheets are attached in the parabolic shape to a basket-like support structure which may be made from strip steel or, to hold costs down, bamboo.

With local artisans in developing countries building the support structure and mounting the plates, the entire production cost of the SK12 is about 110 Euro. Dr. Seifert says the SK cookers were designed for easy production in simple workshops, possibly even in places without electricity. No license fee is charged for using the cooker design.

SK production workshops have been set up in Argentina, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Brazil, Cameroon, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Germany, Ghana, India, Kenya, Madagascar, Peru, Nepal, Nicaragua, Peru, Philippines, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe, with more workshops planned for the near future. Two trained workers can build several SK cookers per day.

Leading the dissemination of the SK line of cookers is a German organization called EG-Solar. Documentation on these cookers is available from EG-Solar, which also is the source for sample cookers and sets of the aluminum reflector panels. (The cookers and panels are produced by another agency, JAGUS, which provides assistance to jobless youth.) EG-Solar can also help set up workshops and train production workers. More than 50 production workers from many parts of the world have been trained. (EG-Solar can be reached at State Technical College Altotting, Neuottinger Str. 64c, D-84503 Altotting, Germany, tel: 08671 96 99 37, fax: 08671 96 99 38, e-mail: EG-SOLAR@t-online.de, web: http://www.eg-solar.de)

Other European development organizations also help communities obtain SK cookers, including an appropriate technology group called WOT at University Twente in the Netherlands and Projektgruppe Solartechnik of the Vocational School at Freilassing, Germany.

At a hospital in Zimbabwe, a Dr. Eder founded a small SK production workshop three years ago, with assistance from EG-Solar. The women accompanying patients (and cooking their meals), as well as local inhabitants of the area, suffered extreme difficulties in finding fuelwood. The workshop now produces four SK cookers per week and the cookers meet almost the total demand for cooking at the hospital.

In Madagascar, a technical training center called SOLTEC produced and distributed 90 SK14 cookers in one year. Dr. Seifert reports that the government of Madagascar is planning to equip 35,000 families with SK cookers in conjunction with a housing program.

ANANDO, a German NGO with a vocational training center in Tangail, Bangladesh, invited a German Technical Studies teacher, Ludolf Bahr, to introduce the SK cooker there. Working with one other volunteer, Mr. Bahr produced 40 SK cookers at a cost of about $80 each. The cost was too high for many of the local people, so the 40 cookers were mainly distributed in exchange for volunteer work.

The European Committee for Solar Cooking Research tested the SK12 in 1994 and had the following comments: "excellent thermal performance for a concentrator Ö easy one-step pot access; tracking easy but ground has to be level; acceptable to operate; cooker not easy to transport Ö moderate risk of skin burns and glare Ö" After some improvements to the SK cookers, follow-up tests in 1997 in South Africa, involving 66 local families who got to try several different cookers for months at a time, have put the SK cookers at about the top of the list for consumer acceptance.

Dr. Seifert believes that the SK cookers are most efficient when used with "haybaskets." (Haybaskets are well-insulated storage containers where a pot of hot food can be safely kept with its heat trapped; partially cooked food that has been heated to cooking temperatures can finish cooking in the haybaskets, making use of the heat already in the food and pot. Using a basket with cotton or wool blankets to cover the pot, with a cushion of hay at the bottom, ensures dry insulation.)

Because the SK cookers cook rapidly, many pots of food can be partially cooked in the SK in sequence and then put to simmer to completion in the haybasket, while the next pot gets its turn on the SK. Dr. Seifert says one SK plus three haybaskets would serve the cooking needs of 10 to 20 people.

An Easier Way to Build Your Own Solar CooKit

SCI's standard CooKit (figure 1) calls for a lot of curves, which can be hard

to make with a hand held blade. Juan Urrutia y Sanz of the Manos Unidas

organization in Spain writes that his group promotes a variation on the CooKit

shape that is easier for many people to make at home. The Manos Unidas version,

called Cocinsol II, is shown in figures 2 and 3. SeŮor Urrutia y Sanz reports

that it cooks as well as the CooKit and actually has more reflective surface

area. SCI's Jay Campbell agrees. Jay is an engineer who has chaired the SCI

Research Committee and who worked on engineering the CooKit for manufacture in

Kenya. (One key advantage of the CooKit's curved shape is that it is easier to

figure out a way to fold it into an album-sized package for easy storage and

transport.) To make your own Cocinsol II, use the shape and dimensions shown in

figure 2. Cardboard is an inexpensive material to use which holds its shape and

is also easy to fold.

SCI's standard CooKit (figure 1) calls for a lot of curves, which can be hard

to make with a hand held blade. Juan Urrutia y Sanz of the Manos Unidas

organization in Spain writes that his group promotes a variation on the CooKit

shape that is easier for many people to make at home. The Manos Unidas version,

called Cocinsol II, is shown in figures 2 and 3. SeŮor Urrutia y Sanz reports

that it cooks as well as the CooKit and actually has more reflective surface

area. SCI's Jay Campbell agrees. Jay is an engineer who has chaired the SCI

Research Committee and who worked on engineering the CooKit for manufacture in

Kenya. (One key advantage of the CooKit's curved shape is that it is easier to

figure out a way to fold it into an album-sized package for easy storage and

transport.) To make your own Cocinsol II, use the shape and dimensions shown in

figure 2. Cardboard is an inexpensive material to use which holds its shape and

is also easy to fold.

However, woven mats or baskets, molded plastics or wood

can be used. The solid lines in the design show where to cut; the dotted lines

show where to fold. Cover the surfaces of one side with shiny material such as

aluminum foil or shiny gift wrap (which will reflect light to the pot at the

center of the cooker).

However, woven mats or baskets, molded plastics or wood

can be used. The solid lines in the design show where to cut; the dotted lines

show where to fold. Cover the surfaces of one side with shiny material such as

aluminum foil or shiny gift wrap (which will reflect light to the pot at the

center of the cooker).

The small picture (figure 3) shows how the Cocinsol II

looks when it is folded into shape for cooking. Place your food in a dark pot

with lid. Put the pot inside a clear, heat-resistant plastic bag or under a

large, inverted, clear glass bowl inside the Cocinsol or CooKit and face the

lower side of the cooker toward the sun. For more about the Cocinsol II, contact

Manos Unidas, Barquillo, 38-3, 28004 Madrid, Spain.

The small picture (figure 3) shows how the Cocinsol II

looks when it is folded into shape for cooking. Place your food in a dark pot

with lid. Put the pot inside a clear, heat-resistant plastic bag or under a

large, inverted, clear glass bowl inside the Cocinsol or CooKit and face the

lower side of the cooker toward the sun. For more about the Cocinsol II, contact

Manos Unidas, Barquillo, 38-3, 28004 Madrid, Spain.

by Dr. A. Jagadeesh, Ph.D.

In India mainly box-type solar cookers are promoted by the government providing subsidy as an incentive. By the end of March, 1998, 451,000 solar cookers were sold. Though the solar cooker had its origins in India (designed by Mr. Ghosh in 1940), its pace has been far from satisfactory. If statistics have any meaning, solar cookers are far behind biogas plants (2.674 million) and improved chulahs (26.498 million) for the countryís population of 980 million!

In innovation theory there are two approaches: Technology-push and Demand-pull. Solar cookers belong to the first category. In India they were promoted by the government mainly for targets rather than for a long-term goal with reliability. It has been proved in many cases (solar cookers are no exception) that wherever subsidies are offered the quality suffers as the main accent will be to minimize the cost. Any device/gadget should meet the userís needs. Nobody uses useless things. Bicycles costing three times that of a solar cooker were never subsidized but millions of them are in use in India today. As such, solar cookers should meet the userís needs (1-3). Also, the report in Rural Energy Journal (4) presents interesting reading; "A majority of the half-million solar cookers sold are in cities, almost none in rural areas where women suffer most from indoor air pollution from cooking. They estimate only 10% are being used or are in working order. Unless the cookers are available in several sizes and price ranges, are lighter and sturdier, they are unlikely to be seen under the sun where they belong."

The main reasons for slow progress of solar cookers in India are:

- For most Indians, cooking and eating are private affairs. Nobody wants to stand in the hot sun to cook food in the open.

- Assuming that progressive women adopt solar cooking, most of the working women go to the office/workplace from 9 AM to 5 PM (when solar radiation is available) and they want to save the weekends for shopping and recreation.

- There is no provision for frying in the box-type solar cookers. No meal is served without fried curries in South India.

- Nobody wants to use two cooking systems, one for frying and another for boiling.

For wider acceptance, the solar cooker designs have to be well developed in relation to the task to be solved and the economic resources of the users. Efforts should be made to design cost-effective and reliable solar cookers with heat storage. Designs of this nature have been used in Australia and Sweden but could not be adopted in India due to prohibitive cost. Until improved solar cookers are available at an affordable price, the best and most simple approach seems to be to use pre-heated water (50 to 60˚C) utilizing solar energy in cooking as it saves considerable fuelwood, kerosene, gas, electricity, etc.

1

E. Biermann, M. Grupp and R. Palmer, Solar Cooker Acceptance in South Africa: Results of a Comparative Field-test, Solar Energy, Vol. 66, No. 6,401, 1999.2

Lanseni Niare, Mali Solar Cooker Project - One Year Later, Home Power #73, 48 Oct/Nov 1999.3

Michael Grupp, Solar Energy in the Aid Context Chances and Pitfalls, Energy in Africa, International Solar Energy Conference Proceedings, Harare, 123, 1993.4

Rural Energy Journal, Energy Environment Group, Vol. 5, 1998.Contact: Dr. A. Jagadeesh, 2/210, First Floor, Nawab Pet, Nellore 524 002, Andhra Pradesh, India, email: a_jagadeesh@yahoo.com

Editorís note: we encourage discussion and constructive debate regarding the role of solar cooking in the world. Feel free, as always, to respond to this or any other article with your thoughts and experiences. Indeed, India has a long tradition in solar cooking--one that will hopefully continue to grow in positive ways. Two of the above-mentioned reasons for slow progress, i.e. not wanting to "stand in the hot sun to cook food in the open" and difficulties for women who work during solar cooking hours, do not necessarily have to be inhibitive. With panel- and many box-type cookers, the temperatures are gentle enough that most foods wonít burn or overcook. Therefore, food can quickly be placed in the cooker and left alone for hours, while the cook retreats to a cooler location or to work.

What it Means for SCI to Receive a $25,000 Contribution

No one would donate $25,000 to an organization without sharing a vision. A vision of what life could be like half a world away. A vision of so many possible futures (and the wherewithal to help choose among them). A vision of how a small nonprofit organization can make a difference in this vast and complex world. A vision that such a donation is a valued investment in people and bright ideas, returning many-fold profits in enriched lives.

Receiving a substantial donation means that someone truly believes in what youíre putting your heart and energy into; that hard work and dedication have been recognized and given a boost. It means that even when formidable challenges loom, there are people behind and beside you, and together anything is possible.

To the anonymous donor who graciously shared his or her resources with the solar cooking community, We at SCI salute your kindness and vision!

by Joe Radabaugh

Through my book "Heavenís Flame: a Guide to Solar Cookers," I share my experience with solar cookers since the mid-1970s. The book also contains information about my cooker, the SunStar, which can be seen on the Solar Cooking Archives (http://solarcooking.org). The SunStar holds a unique place in the collection of available solar cookers. It is built with the simple recyclable materials of slower cookers, yet its power for cooking approaches that of some commercial models.

My solar work has been a hobby of love, but also a source of income during the sunny months. In the early years I traveled around showing the power of cooking with the sun, and offering one-page plans for $1 or less. In those days not many people had heard of solar cooking, and the sight of boiling beans heated with the sun was awe-inspiring. Unfortunately, I have come to a crossroads in my solar cooking activism--I must either upgrade my efforts or tone down my work. Since my book came out I have spent much of my time discussing solar cooking with novices and experienced cooks alike. The sure volumes of questions I receive show me that we are part of a healthy, growing grassroots movement. The result, though, is that I have not had as much time to do shows and earn an income.

I have begun the rather lengthy process of forming a nonprofit organization in hopes that this will allow me to generate some much-needed funding. If you are interested in sponsoring an expanded educational effort, or have any suggestions, please contact me at P.O. Box 111, Mt. Shasta, California 96067, USA, email: rada8@yahoo.com. For more information on my work, I suggest ordering my book at http://www.homepower.com or by calling (800) 707 6585.

Solar Energy International (SEI) will hold a workshop titled "Renewable Energy for the Developing World" June 26-30 in Carbondale, Colorado, USA. Participants will learn how to implement successful sustainable development projects with renewable energy. Effective technology transfer methods will be presented, as well as setting up infrastructure and the economics and financing of renewable energy projects. Case studies will be presented on solar cooking, rural household electrification, rural health care and micro-enterprises utilizing renewable energy. Cost is US $500. SEI will also hold their 5th annual Carbondale Solar Potluck on July 4. For more information write to P.O. Box 715, Carbondale, CO 81623, USA, or visit their website at http://www.solarenergy.org/.

International Standards for Testing Solar Cookers

Dr. Paul A. Funk

USDA Agricultural Research Service

P.O. Box 578, Mesilla Park, NM 88047, USA

tel: 505-526-6381

fax: 505-525-1076

Historic development of the present standard

The Test Standard Committee convened 7 January 1997 (during the Third World Conference on Solar Cooking sponsored by Avinashilingam University and SCI).

Some of the people attending the first meeting included:

- Mr. Bashir Ahmad

- Mr. G.K. Bhide

- Dr. Paul A. Funk

- Dr. R.P. Goswami

- Mr. R. Jayaprakash

- Dr. S. Jayaraman

- Mr. Kishore Mariwala

- Mr. N.M. Naher

- Prof. Shyam Nandwani

- Dr. Rachel Oommen

- Prof. A.B. Pandit

- Mr. Shirish B. Patel

- Mr. Sharad M. Prasad

- Mr. R.L. Sawhnei

- Dr. Wolfgang Scheffler

- Dr. A.K. Singhal

- Mr. C.E. Sooriamoorth

Our starting point was our agreement that a single, simple figure representing the performance of a solar cooker would help consumers to select an oven for their own use. Cooking power (in Watts) was chosen because it reflects both capacity and rate. The Watt is a unit of measure of power that is familiar to many people. To find the cooking power one only needs to measure the change in temperature of water over time.

During the first meeting five additional points were agreed upon:

- Test method: Place a thermocouple 10 mm above bottom center of pot(s).

- Test range: Water temperature from 40 to 95įC.

- Test conditions: Ambient air temperature between 20 and 35įC.

- Test conditions: Wind speed less than 2.5 m/s.

- Loading rate: 7 liters per square meter solar intercept area. This loading rate is representative of rates cited in previous publications.

During the second meeting on January 8th, additional points were discussed:

- Definition of solar intercept area (agreed it must include reflectors).

- Should we measure insolation with respect to the cooker or the sun angle?

- Standard value for insolation (800 W/m2 was agreed upon).

- Sky conditions (standard deviation of 100 W/m2 was agreed upon).

- Test timeframe (10:00 to 14:00 solar time).

- Tracking frequency (one hour was suggested as beneficial to the consumer).

Many of the participants corresponded over the months following the conference. The resulting draft benefited from a collective experience of decades of solar cooker testing. Preparing the draft for publication added two cycles of peer review, further refining it.

Summary of the present standard

(Note that there have been some changes to the items presented above.)

Beforehand: Obtain lightweight aluminum pots for the cooker to be tested if

none are provided. Paint the outside flat black (chalkboard paint is

recommended). Mount thermocouples (temperature measuring devices) in each pot so

the junction is at the center, 10 mm (3/8 in.) above the bottom. Run the

thermocouple wires through a hole above the water line, inside a protective

plastic sleeve so the wires will not be bent repeatedly. Calculate the zenith

angle (the included angle between the sunís rays and vertical) for the two

hours before and after solar noon on the anticipated day of the test. Measure

the intercept area of the cooker system (including reflectors) perpendicular to

beam radiation at that calculated angle. The easiest way to determine intercept

area is to hold a tape measure or yard stick so a pencil pointing at the sun is

perpendicular to the measuring tape. Then move the measuring tape so the shadow

of the zero end just touches the top of the cooker-reflector system. Drag your

finger down the tape until the shadow made by your finger touches the bottom of

the cooker-reflector system. This is the "height" of the solar cooker

as seen by the sun -- call it sun-apparent height if that helps. The width

(found by normal means) times the sun-apparent height equals the solar intercept

area.

Beforehand: Obtain lightweight aluminum pots for the cooker to be tested if

none are provided. Paint the outside flat black (chalkboard paint is

recommended). Mount thermocouples (temperature measuring devices) in each pot so

the junction is at the center, 10 mm (3/8 in.) above the bottom. Run the

thermocouple wires through a hole above the water line, inside a protective

plastic sleeve so the wires will not be bent repeatedly. Calculate the zenith

angle (the included angle between the sunís rays and vertical) for the two

hours before and after solar noon on the anticipated day of the test. Measure

the intercept area of the cooker system (including reflectors) perpendicular to

beam radiation at that calculated angle. The easiest way to determine intercept

area is to hold a tape measure or yard stick so a pencil pointing at the sun is

perpendicular to the measuring tape. Then move the measuring tape so the shadow

of the zero end just touches the top of the cooker-reflector system. Drag your

finger down the tape until the shadow made by your finger touches the bottom of

the cooker-reflector system. This is the "height" of the solar cooker

as seen by the sun -- call it sun-apparent height if that helps. The width

(found by normal means) times the sun-apparent height equals the solar intercept

area.

Morning of test: Carefully weigh 7 kg of water per square meter intercept

area and divide it equally between the pots if there is more than one pot. (Make

sure the thermocouple junctions are submerged!) Connect the thermocouples

together in parallel to obtain a physical average of the temperatures of each

pot if there is more than one.

Morning of test: Carefully weigh 7 kg of water per square meter intercept

area and divide it equally between the pots if there is more than one pot. (Make

sure the thermocouple junctions are submerged!) Connect the thermocouples

together in parallel to obtain a physical average of the temperatures of each

pot if there is more than one.

The test begins when water temperature reaches 40įC and concludes when water reaches 90įC. Record wind speed, direct beam insolation (light energy from the sun measured on a surface perpendicular to the sunís rays, usually in W/m2), ambient and water temperatures at least every ten minutes. Track the sun as required, noting when the cooker was repositioned.

If the wind exceeds 2.5 m/s or averages more than 1 m/s during the test, try

again. If ambient air temperature exceeds 35įC or falls below 20įC, try again.

If insolation exceeds 1100 W/m2, falls below 450 W/m2, or

changes more than 100 W/m2 between two consecutive ten-minute

intervals, try again. These limits are to minimize environmental effects, so

data from different locations and dates can be compared fairly. (In other words,

you want a calm, clear day.)

If the wind exceeds 2.5 m/s or averages more than 1 m/s during the test, try

again. If ambient air temperature exceeds 35įC or falls below 20įC, try again.

If insolation exceeds 1100 W/m2, falls below 450 W/m2, or

changes more than 100 W/m2 between two consecutive ten-minute

intervals, try again. These limits are to minimize environmental effects, so

data from different locations and dates can be compared fairly. (In other words,

you want a calm, clear day.)

Average the insolation, ambient, and water temperatures for each ten-minute interval.

Calculate cooking power for each interval as follows: Multiply the total mass of water in the cooker (kg) by the change in temperature in ten minutes (C) and by the heat capacity of water (4186 J/kg C). Divide the result by 600 seconds, and you have power (W = J/s).

Standardize the cooking power of each interval by multiplying by 700 W/m2 and dividing by the average insolation (W/m2) of that interval. Find the temperature difference for each interval by subtracting the ambient temperature from the average water temperature.

Plot the standardized cooking power (vertical axis) over the temperature difference (horizontal axis) for each interval. Plot the linear regression. If the linear regression has a coefficient of correlation (R2) less than 0.9, repeat the test. The point where this line crosses a temperature difference of 50įC is the standard cooking power (W). In the test report give the dates, wind, insolation, regression equation, regression correlation coefficient and standard power.

Example of the present standard

A box-type solar cooker holding five small pots was tested at two different locations eighteen months apart. In the first test data points were recorded by hand. In the second test an electronic data logger recorded temperatures and insolation every minute. In the second test a ten-minute interval was calculated every minute, so consecutive intervals overlapped each other. This merely provided more observations. There were differences in sun angle and ambient temperature due to season, and elevation and clearness due to location. However, the results indicate repeatability is fairly good (the difference is attributed to deterioration in the plastic glazing caused by dirt and scratches).

A plot of the two tests is provided in figure 1. The standard cooking power was 46 W in May of 1997 (Tucson, AZ) and 37 W in November of 1998 (Las Cruces, NM). More detail on the solar cooker test standard is available in the article Evaluating the International Standard Procedure for Testing Solar Cookers and Reporting Performance, Solar Energy, Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 1-7, 2000. There are many people that have contributed to this present standard. I would especially like to acknowledge the pioneers of the first standard, S. C. Mullick, T. C. Kandpal and A. K. Saxena.

Figure 1. Example of the international standard applied to the same cooker in two different locations eighteen months apart.

- Anna Scherzer

Solar Cooker Review

Solar Cooker Review is published two or three times a year, with the purpose of presenting solar cooking information from around the world. Topics include solar cooker technology, dissemination strategies, educational materials, and cultural and social adaptations. From time to time we cover related topics such as womenís issues, wood shortages, health, nutrition, air pollution, climatic changes, and the environment.

Solar Cooker Review is sent to those who contribute money or news about solar cooking projects. The suggested subscription price is $10/year. Single copies are sent free to select libraries and groups overseas.

We welcome reports and commentary related to solar cooking for possible inclusion. These may be edited for clarity or space. Please cite sources whenever possible. We will credit your contribution. Send contributions to Solar Cookers International, 1919 21st St. Ste. 101, Sacramento, CA 95811-6827, USA. You may also send them by fax 916 455 4498, or email info@solarcookers.org.

Solar Cooker Review

is compiled and edited by the staff of Solar Cookers International, with layout provided by IMPACT Publications located in Medford, OR, USA. SCI is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization whose mission is to spread solar cooking to benefit people and environments.Solar Cookers International

1919 21st Street, #101

Sacramento, CA 95811, USA

Tel: 916-455-4499

Fax: 916-455-4498

Email: info@solarcookers.org

Board of Directors

- David Anderson

- Consuella Brown

- Beverlee Bruce, Ph.D.

- Paul Funk, Ph.D.

- Christopher Gronbeck

- Linda Helm Krapf

- Barbara Knudson, Ph.D.

- Lorrie McCurdy

- Robert Metcalf, Ph.D.

- Virginie Mitchem

- Barby Pulliam

- Judith Ricci, Ph.D.

- Meredith Richardson

- John Roche

- Mary Ann Smith

- Claude Thau

- Elvira Williams

SCIís mission is to spread solar cooking to benefit people and environments